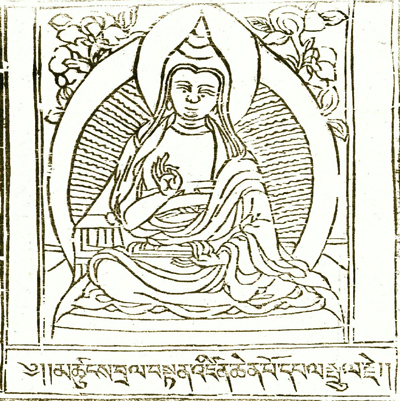

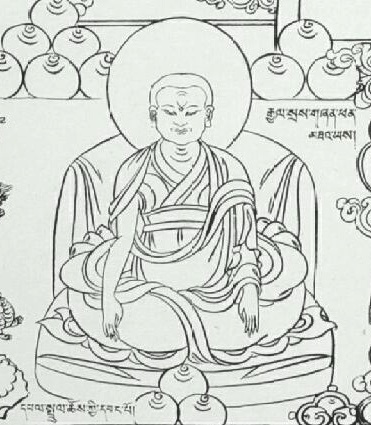

Dza Patrul Orgyen Jigme Chokyi Wangpo

Dza Patrul Orgyen Jigme Chokyi Wangpo (rdza dpal sprul o rgyan ‘jigs med chos kyi dbang po), commonly known as Patrul, short for “Pelge Tulku” (meaning the Pelge incarnation),  was born into the Gyatok (rgyal thog) family in Getse Dzachuka (dge rtse rdza chu kha) in northern Khams, in the male-earth-dragon year of the fourteenth rab ‘byung (1808). His father, from the Mukpo clan (smug po gdong) in Upper Getse, was named Gyatok Lhawang (rgyal tog lha dbang) and his mother was called Dolma (sgrol ma).

was born into the Gyatok (rgyal thog) family in Getse Dzachuka (dge rtse rdza chu kha) in northern Khams, in the male-earth-dragon year of the fourteenth rab ‘byung (1808). His father, from the Mukpo clan (smug po gdong) in Upper Getse, was named Gyatok Lhawang (rgyal tog lha dbang) and his mother was called Dolma (sgrol ma).

Dola Jigme Kelzang (rdo bla ‘jigs med skal bzang, d.u.) recognized Patrul as the incarnation of Pelge Lama, Samten Puntsok (dpal dge’i bla ma bsam gtan phun tshogs, d. 1807); his lifelong title, Patrul, comes from an abbreviation of Palge Tulku. The first Dodrupchen, Jigme Trinle Ozer (rdo grub chen 01 ‘jigs med phrin las ‘od zer, 1745-1821) confirmed the recognition and gave Patrul the religious name Orgyen Jigme Choki Wangbo. Around the age of twenty, however, Patrul closed his residence at Samten Puntsok’s monastic property (the Pelge Labrang) and renounced his material rights as an incarnate lama, instead choosing to live the life of a wandering student, teacher and hermit.

Patrul was also considered by many to be the speech emanation of Jigme Lingpa(‘jigs med gling pa, 1729/30-1798). In a biographical hymn to Patrul, Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (‘byams dbyangs mkhyen brtse’i dbang po, 1820-1892) also alludes to Patrul being an incarnation of Śāntideva (7th century), the Indian siddhaShabari, and Aro Yeshe Jungne (a ro ye shes ‘byung gnas, 13th c.), and to his being an emanation of Dukngel Rangdrol (sdug bsngal rang grol), a form of the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara.

Patrul received monk’s ordination from KhenpoSengtruk Pema Tashi (mkhan po seng phrug pad+ma bkra shis) of Dzogchen monastery sometime after leaving the Pelge Labrang, it seems, and studied the sutras and tantras with many of the greatest teachers of the old translation school in Khams. For example, he studied Shantideva’s Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra,Longchenpa’s Ngelso Korsum (ngal gso skor gsum), the Guhyagarbhatantra, and the secular sciences from Dola Jigme Kelzang, Jigme Ngotsar (‘jigs med ngo mtshar, b. 1730), and Gyelse Zhenpen Taye (rgyal sras gzhan phan mtha’ yas, 1800-1855).

Patrul received monk’s ordination from KhenpoSengtruk Pema Tashi (mkhan po seng phrug pad+ma bkra shis) of Dzogchen monastery sometime after leaving the Pelge Labrang, it seems, and studied the sutras and tantras with many of the greatest teachers of the old translation school in Khams. For example, he studied Shantideva’s Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra,Longchenpa’s Ngelso Korsum (ngal gso skor gsum), the Guhyagarbhatantra, and the secular sciences from Dola Jigme Kelzang, Jigme Ngotsar (‘jigs med ngo mtshar, b. 1730), and Gyelse Zhenpen Taye (rgyal sras gzhan phan mtha’ yas, 1800-1855).

He received Nyingtik instructions from Gyelse Zhenpen Taye and the Fourth Dzogchen Drubwang, Mingyur Namkai Dorje (rdzogs chen grub dbang 04 mi ‘gyur nam mkha’i rdo rje, 1793-1870). Shechen Wontrul Tutob Namgyel (zhe chen dbon sprul mthu stobs rnam rgyal, 1787-1854) gave Patrul a transmission for the Kanjur (bka’ ‘gyur) and taught him grammar. Finally, the great treasure revealerChokgyur Lingpa (mchog gyur bde chen gling pa, 1829-1870), upon entrusting Patrul as the custodian (chos bdag) of his Demchog Sanggye Nyamjor (bde mchog sangs rgyas mnyam sbyor) revelation, gave him all of the appropriate empowerments, transmissions and instructions for the cycle.

Patrul’s root guru was the hermit Jigme Gyelwai Nyugu (‘jigs med rgyal ba’i myu gu, 1765-1842), one of the two primary lineage-holders of Jigme Lingpa‘s Longchen Nyingtik revelation. During Patrul’s formative years with his guru in their common home-region of Dza, Patrul is said to have heard Gyelwai Nyugu deliver oral instructions on the preliminary practices for the Longchen Nyingtik no less than twenty five times. Patrul later wrote down these colorful counsels while in retreat in the Yamāntaka cave above Dzogchen monastery, thus creating his beloved workWords of My Perfect Teacher (kun bzang bla ma’i zhal lung) In the latter part of his life, Patrul chose to spend much of his time in and around Gyelwai Nyugu’s monastery Dza Gyalgon (rdza rgyal dgon).

While Gyelwai Nyugu first introduced Patrul to the nature of mind, Patrul’s full-blown awakening to unobstructed awareness (zang thal gyi rig pa) came at the hands of Do Khyentse Yeshe Dorje (mdo mkhyen brtse ‘jigs med ye shes rdo rjes, 1800-1866). A story that is often told relates the moment in which this occurred: one day, Patrul met Do Khyentse outside of his tent. The infamous hunter-yogi grabbed Patrul by the hair and tossed him to the ground. Patrul, smelling alcohol on the master’s breath, thought to himself that Do Khyentse was surely acting as he was due to the harmful influence of alcohol. Do Khyentse, sensing Patrul’s critical thoughts, scolded him, calling Patrul an “Old Dog,” spitting on him, and showing him his pinky finger in disgust before walking away. Patrul immediately realized his mistake, recognizing that Do Khyenste had in fact given him a powerful instruction meant to lead him to an unmediated experience of the nature of mind. Patrul straightened his posture and immediately experienced a direct realization of unhindered awareness. In memory of this seminal event, Patrul, in typically humble fashion, often referred to himself as “Old Dog” (khyi rgan).

While Gyelwai Nyugu first introduced Patrul to the nature of mind, Patrul’s full-blown awakening to unobstructed awareness (zang thal gyi rig pa) came at the hands of Do Khyentse Yeshe Dorje (mdo mkhyen brtse ‘jigs med ye shes rdo rjes, 1800-1866). A story that is often told relates the moment in which this occurred: one day, Patrul met Do Khyentse outside of his tent. The infamous hunter-yogi grabbed Patrul by the hair and tossed him to the ground. Patrul, smelling alcohol on the master’s breath, thought to himself that Do Khyentse was surely acting as he was due to the harmful influence of alcohol. Do Khyentse, sensing Patrul’s critical thoughts, scolded him, calling Patrul an “Old Dog,” spitting on him, and showing him his pinky finger in disgust before walking away. Patrul immediately realized his mistake, recognizing that Do Khyenste had in fact given him a powerful instruction meant to lead him to an unmediated experience of the nature of mind. Patrul straightened his posture and immediately experienced a direct realization of unhindered awareness. In memory of this seminal event, Patrul, in typically humble fashion, often referred to himself as “Old Dog” (khyi rgan).

While Patrul rarely gave empowerments or conducted public ritual ceremonies, he nonetheless taught extensively in the Derge region of Khams—most notably at Dzogchen’s Shri Senge monastic college and at Katok monastery—and in the Northern regions of Dza and Golok, including at Dodrubchens’ monastery of Yarlung Pemako (sometime between 1851 and 1855). He commonly instructed students on Guhyagarbha using Longchenpa‘s Chokchu Munsel commentary (phyogs bcu’i mun sel), and repeatedly taught Longchenpa’s Ngelso Korsum, Jigme Lingpa‘s Yonten Dzo (yon tan mdzod), Ngari Paṇchen‘s (mnga’ ri paN chen pad+ma dbang rgyal, 1487-1542) Domsum Namnge (sdom gsum rnam nges), and the inner yoga and personal instructions for the Longchen Nyingtik. At Dzogchen’s monastic academy, Patrul also taught on the Abhisamayālaṃkāra, Mulamadhyāmakakarika, Mahāyānasutralankara, and the Abhidharmakośa.

Patrul is perhaps most famous for his perpetual lessons on Śāntideva’s Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra, Karma Chakme‘s (karma chags med, 1613-1678) Dechen Monlam (bde chen smon lam), the Maṇi Kambum (maNi bka’ ‘bum), and the chanting of Avalokiteśvara’s six-syllable mantra (oṃ maṇi padme hūṃ). To name but one consequential example, Patrul spent five days teaching Mipam Gyatso (mi pham rgya mtsho, 1846-1912) the Ninth Chapter on wisdom from the Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra, teachings which Mipam credits for guiding his famous and controversial commentary on the chapter. Patrul also taught the above-mentioned materials during his travels in nomadic regions of Dza, Golok, and Serta, where he greatly spread the practice of chanting the mantra and praying for rebirth in the Sukhāvati Pure Land of the Buddha Amitābha. Patrul was also supposedly successful at curbing the practice of offering meat to lamas, limiting hunting and curtailing banditry in these regions.

Patrul’s collected works, in six volumes, was assembled by his disciple and attendant Gemang Won Rinpoche Orgyen Tendzin Norbu (dge mang dbon rin po che o rgyan bstan ‘dzin nor bu, b. 1851) and published under the auspices of Khenpo Zhenga, Zhenpen Chokyi Nangwa (gzhan phan chos kyi snang ba, 1871-1927) at Dzogchen monastery. His three most acclaimed works are a large commentary on the Abhisamayālaṃkāra, the previously mentioned Words of My Perfect Teacher, and a text entitled the Khepa Shri Gyalbo (mkhas pa shri rgyal po) – a brief but profound instruction on generating and stabilizing the realization of the nature of one’s mind, based on the Tsiksum Nedek (tshig gsum gnad brdegs degs) ascribed to Garab Dorje (dga’ rab rdo rje).

In addition, Patrul’s works testify to his fascination with the Buddhist path in its various permutations. He wrote both commentaries on and analytical outlines of Indian and Tibetan renditions of the path, and composed free-standing investigations of path-related topics ranging from monastic discipline to the stages of bodhisattva practice. Patrul also composed dozens of life-advice texts (zhal gdams and gtam tshogs), a great many of which offer condensed versions of the path, often emphasizing simple yet all-encompassing “essential points” of the practice, such as devoting oneself to one’s guru, generating the wish to serve others, or looking at one’s own mind. Patrul’s life-advice compositions include the colorful Pema Tselgi Dokar (padma tshal gyi zlos gar), a drama consisting of dharma instructions to a bee who is overcome with sorrow at the loss of his lover, and the Dampai Nyingnor (thog mtha’ bar gsum du dge ba’i gtam dam pa’i snying nor), a lyrical instruction on the entirety of the path through the prism of Avalokiteśvara’s six-syllable mantra. Patrul’s extraordinarily witty and illustrative writing substantiates his reputation as a brilliant orator and spiritual guide.

Patrul dedicated his life to religious activities, large and small. He meditated extensively in retreat caves, the benefit of which he repeatedly extols in his advice compositions. He spent nearly a decade of his life as a hermit in the Do valley (rdo)in Serta with his heart disciple Nyoshul Lungtok Tenpai Nyima (smyo shul lung rtogs bstan pa’i nyi ma, b. 1830), at times living in the forest on little more than barley (and apparently, for a short time, surviving exclusively on tea made from the roots of nearby bushes!). He also repaired the Dobum Chenmo (rdo ‘bum chen mo) built by his predecessor Samten Puntsok, a massive stone wall inscribed ten-thousand times with Avalokiteśvara’s six-syllable mantra.

There are also plenty of examples of his indiscriminate devotion to the wellbeing of all. Patrul once saved the life of a beggar who had stolen money offerings from a public ritual, and he rescued innumerable animals from certain death by outlawing meat offerings to lamas, teaching the harm of hunting, and modeling the virtues of vegetarianism.

Patrul’s legacy survives in his successful spread of the Longchen Nyingtik teachings throughout Kham, not to mention his often-cited status as a model of bodhisattva activity for contemporary practitioners. Some of his primary disciples were: Nyoshul Lungtok Tenpai Nyima, Gemang Won Rinpoche, Gyelrong Tendzin Drakpa (rgyal rong bstan ‘dzin grags pa), and Minyak Kunzang Sonam (mi nyag kun bzang bsod nams, 1823-1905). Other notable students include Mipam, the second and third Dodrubchen incarnations, Adzom Drukpa Pawo Dorje (a ‘dzom ‘brug pa dpa’ bo rdo rje, 1842-1924), and Khenpo Kunzang Pelden (mkhan chen kun bzang dpal ldan, 1862-1943) who wrote the most extensive biography of his teacher.

Patrul died on the eighteenth day of Saga (the fourth month) of the fire-pig year of the fifteenth rab ‘byung (1887) in the presence of his doctor and two attendants. His funeral was overseen by his attendant Gemang Won Rinpoche.

Source: The Treasury of lives

Leave a Reply