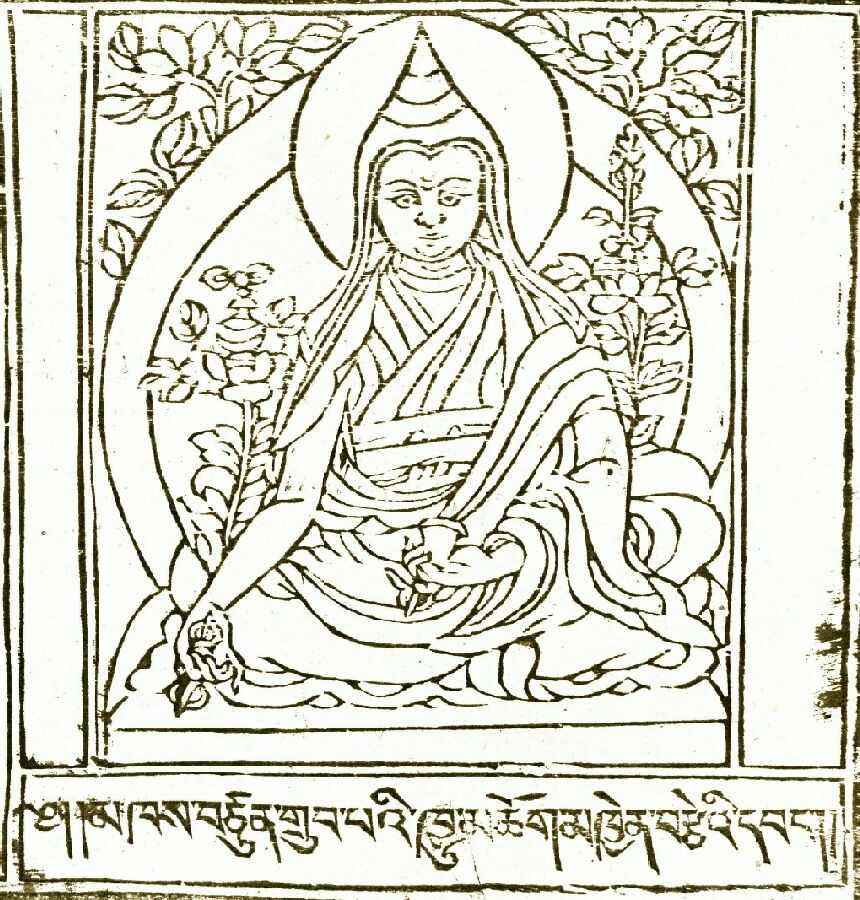

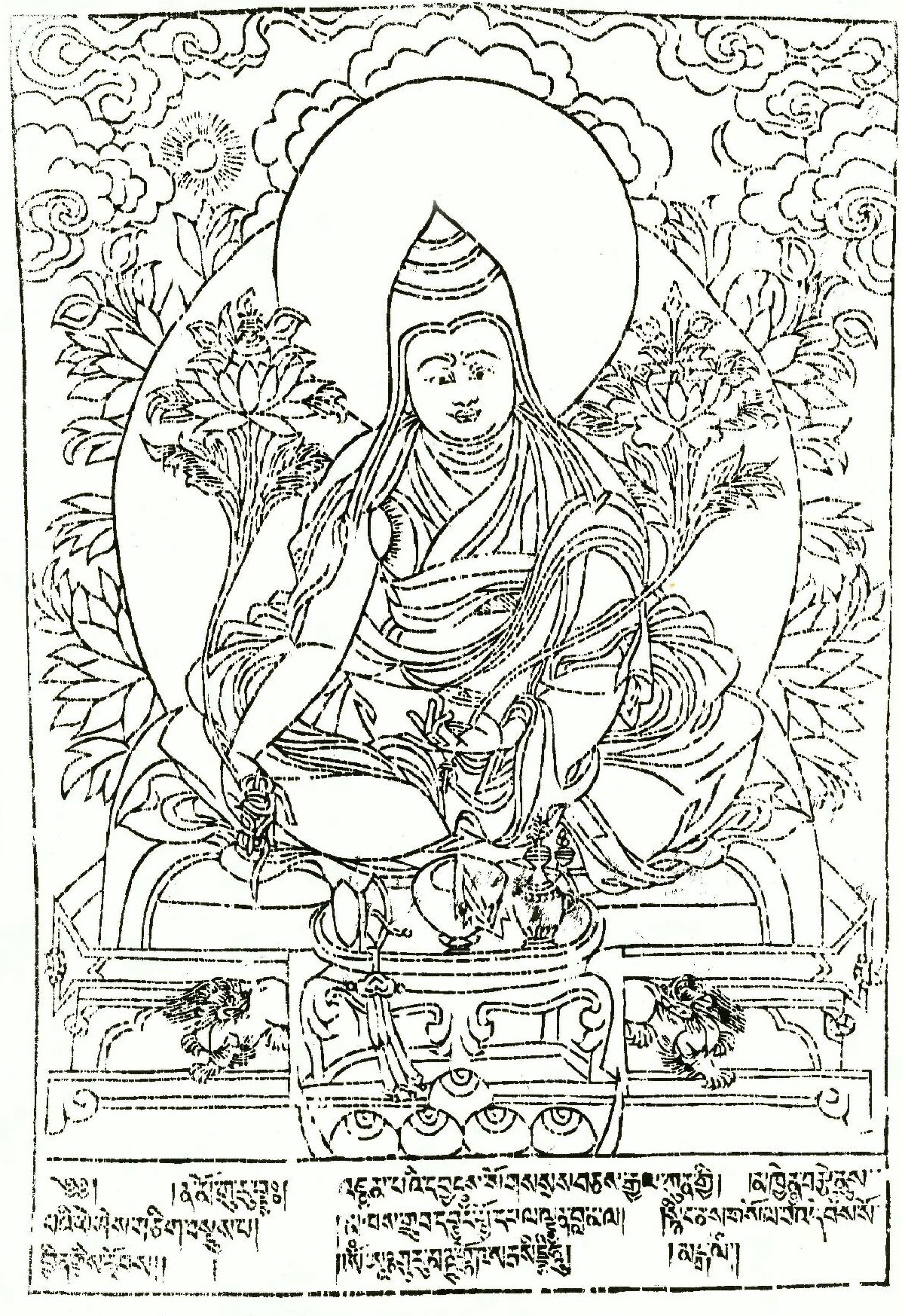

Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo

Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo (‘jam dbyangs mkhyen brtse’ dbang po) was born in 1820 in the village of Dilgo (dil mgo) in the Terlung (gter klung) valley to the southeast of the Dege capital.  His father was Rinchen Namgyel (rin chen rnam rgyal), and his mother was named Sonam Tso (bsod nams ‘tsho). His clan was Shingkhamga (shing khams sga) and his lineage was the Nyo (myos). A lama named Sharchen Rinchen Mingyur Gyeltsen (shar chen rin chen mi ‘gyur rgyal mtshan, d.u.) named him Rinchen Wanggyal (rin chen dbang rgyal), and later his father gave him the name Tsering Dondrub (tshe ring don grub). He had at least two brothers: Kelzang Dorje (skal bzang rdo rje) and Gyurme Dondrub (‘gyur med don grub).

His father was Rinchen Namgyel (rin chen rnam rgyal), and his mother was named Sonam Tso (bsod nams ‘tsho). His clan was Shingkhamga (shing khams sga) and his lineage was the Nyo (myos). A lama named Sharchen Rinchen Mingyur Gyeltsen (shar chen rin chen mi ‘gyur rgyal mtshan, d.u.) named him Rinchen Wanggyal (rin chen dbang rgyal), and later his father gave him the name Tsering Dondrub (tshe ring don grub). He had at least two brothers: Kelzang Dorje (skal bzang rdo rje) and Gyurme Dondrub (‘gyur med don grub).

At the age of three the boy met Tartse Khenchen Jampa Kunga Tendzin (thar rtse mkhan chen byams pa kun dga’ bstan ‘dzin, 1776-1862), who was in Dege serving as court chaplain. The following year, or possibly the next, Tartse Khenchen gave him his lay vows. By the age of eight he had studied reading and writing with a lama named Chaga Khenpo Pema Tashi (b’ ga mkhan po pad+ma bkra shis), and medicine with the Dege court physician, Chodrak Gyatso (chos grags rgya mtsho).

In his youth he the Sakya visited Dzongsar (rdzong sar) monastery, in the Mesho (sman shod) valley to the immediate west of Terlung, where his family had long-standing connections. He also visited Katok (kaH thog), a large Nyingma monastery to the south where he met his uncle, Mokton Tulku Sangdak Chenpo (rmog ston sprul sku gsang bdag chen po, d.u.), an important incarnate lama of the monastery, who gave him the name Jigme Khyentse Dogar (‘jigs med mkhyen brtse’i zlos gar). There he also received a blessing from Pema Chogyel Tulku Jangchub Chokyi Nyima (pad+ma chos rgyal sprul sku byang chub chos kyi nyi ma, d.u.), who prophesied that he would have a long life.

When the boy was twelve Tartse Khenpo identified him as the reincarnation of Tartse Khenchen Jampa Namkha Chime (thar rtse mkhan chen byams pa nam mkha’ ‘chi med, 1765-1820), and gave him the name Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo Kunga Tenpai Gyeltsen Pelzangpo (‘jam dbyangs mkhyen brtse’ dbang po kun dga’ bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan dpal bzang po). Tartse Khenpo urged the boy’s father to send him to Ngor Monastery in Tsang for training, but the father declined, refusing to trade his son for the silver then being offered. However, he said he was willing to allow his son to enter into the religious life should the boy later show interest. From then on Khyentse Wangpo was known as Tartse Tulku (thar rtse sprul sku) or simply Shabdrung (zhabs drung). Later he came to be identified as the mind incarnation of the famous Nyingma treasure revealer Jigme Lingpa (‘jigs med gling pa, c.1730-1798), but how late this identification was made — whether it was during or after his life — is not clear.

When the boy was twelve Tartse Khenpo identified him as the reincarnation of Tartse Khenchen Jampa Namkha Chime (thar rtse mkhan chen byams pa nam mkha’ ‘chi med, 1765-1820), and gave him the name Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo Kunga Tenpai Gyeltsen Pelzangpo (‘jam dbyangs mkhyen brtse’ dbang po kun dga’ bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan dpal bzang po). Tartse Khenpo urged the boy’s father to send him to Ngor Monastery in Tsang for training, but the father declined, refusing to trade his son for the silver then being offered. However, he said he was willing to allow his son to enter into the religious life should the boy later show interest. From then on Khyentse Wangpo was known as Tartse Tulku (thar rtse sprul sku) or simply Shabdrung (zhabs drung). Later he came to be identified as the mind incarnation of the famous Nyingma treasure revealer Jigme Lingpa (‘jigs med gling pa, c.1730-1798), but how late this identification was made — whether it was during or after his life — is not clear.

At the age of twenty Khyentse Wangpo left Kham for Tibet, studying at both Tartse and Ngor monasteries. There he received the Cakrasaṃvara and Hevajra from a brother of Tartse Khenpo Namkha Chime, among other transmissions of Sakya teachings. Despite his Sakya incarnation identification, he took ordination at age twenty-one at Mindroling Monastery, with Minling Khenchen Gyurme Rigdzin Zangpo (smin gling mkhan chen ‘gyur med rig dzin bzang po, d.u.), from whom he received the name Kunga Tenpai Gyeltsen (kun dga’ bstan pa’i rgyal mtshan). At Mindroling he received transmission of Yangdak Heruka in the So lineage (so lugs yang dag) and the Terdak Lingpa (gter bdag gling pa, 1646-1714) treasure cycle Rigdzin Tugtik (rig ‘dzin thugs thug).

Khyentse Wangpo is well-known for having studied with many of the leading lamas of his day in both Tibet and Kham. Before leaving Kham he had gone to Shechen to give at long-life empowerment, at the request of the Dege King, Damtsig Dorje (dam tshig rdo rje, 1811-1852), to Shechen Wontrul Gyurme Tutob Namgyel (zhe chen dbon sprul ‘gyur med mthu stobs rnam rgyal, 1787-1854), from whom he received Māyājāla teachings and empowerments in return. At the age of twenty he received transmission in the Longchen Nyingtik (klong chen snying thig) from Jigme Gyelwai Nyugu (‘jigs med rgyal ba’i myu gu, 1765-1842), who was traveling through the Terlung Valley. Although the Longchen Nyingtik was not one of his primary practices, he figures large in the transmission history of the treasure cycle.

Other prominent lamas that he studied with include:Shechen Paṇḍita Jamyang Gyepai Lodro (zhe chen paNDita ‘jam dbyangs dgyes pa’i blo gros, d.u.), theSecond Dzogchen Khenrab Zhenpen Taye (rdzogs chen mkhan rabs 02 gzhan phan mtha’ yas, 1800-1855), the Fourth Dzogchen Tulku Mingyur Namkhai Dorje (rdzogs chen 04 mi ‘gyur nam mkha’i rdo rje, 1793-1870), the Thirty-fourth Sakya Trichen Pema Dundul Wangchuk (sa skya khri chen 34 pad+ma bdud ‘dul dbang phyug, 1792-1853), the Thirty-fifth Sakya Trichen Dorje Rinchen (sa skya khri chen 35 rdo rje rin chen, 1819-1867), Zhalu Ribug Tulku Losel Tenkyong (zhwa lu ri sbug sprul sku blo gsal bstan skyong, b. 1804), the Forty-seventh Ngor Khenchen Jampa Kunga Tendzin (ngor mkhan chen 47 byams pa kun dga’ bstan ‘dzin, 1776-1862), and Pelyul Dongak Tendzin (dpal yul mdo sngags bstan ‘dzin, 1830-1892).

At the age of twenty-four Khyentse Wangpo returned to Kham with the Fifty-first Ngor Khenchen, Jampel Zangpo (ngor mkhan chen 51 ‘jam dpal bzang po, 1789-1864), and took up residence at Dzongsar monastery, in the Tashi Latse (bkra shis lha rtse) residence, which later came to be called the Khyentse Labrang (mkhyen brtse bla brang). For the next four years, in accordance with the Ngor custom, he practiced tantra, such as Hevajra, the three classes of Kriya tantra, and so forth.

At the age of twenty-nine, in 1848, Khyentse Wangpo traveled again to Tibet with the Ngor Khenchen, where he remained until the beginning of the 1850s.

Over the decade of the 1850s Khyentse Wangpo collaborated so closely with two men that the three continue to be referred to as the Khyen Kong Chog Desum (mkhyen kong mchog sde gsum), meaning “the triumvirate of Khyentse Wangpo, Kongtrul Lodro Taye, and Chokgyur Lingpa. Jamgon Kongtrul Lodro Taye(‘jam mgon kong sprul blo gros mtha’ yas, 1813-1899) was a prominent tulku at the Karma Kagyu monastery a half a day’s walk from Dzongsar. Chokgyur Lingpa (mchog gyur gling pa, 1829-1870) was an up-and-coming treasure revealer active in the Dege and Nangchen regions of Kham who relied on both Khyentse and Kongtrul for his initial affirmation of legitimacy.

Khyentse Wangpo met Jamgon Kongtrul at the end of 1840, when he went to Pelpung to receive teachings from the elder lama on Chandragomin’s grammar. They met again before Jamyang Khyentse went to Tibet the second time. Khyentse Wangpo’s beloved elder brother, Gyurme Dondrub had passed away in Tibet, and it appears that in his grief Khyentse Wangpo turned to his growing friendship with Jamgon Kongtrul for companionship. He went to Pelpung for an extensive transmission of Jonang teachings, including the complete works of Tāranātha and the Kālacakra. Jamgon Kongtrul continued his transmission of Jonang teachings to Khyentse Wangpo after the later returned from Tibet in the early 1850s, giving Tāranātha’s Drubta Rinjung (sgrub thabs rin ‘jung). At the time Khyentse Wangpo gave Jamgon Kongtrul a complete set of Tāranātha’s writings.

Khyentse Wangpo appears to have first met Chokgyur Lingpa when Jamgon Kongtrul sent the young treasure revealer for evaluation sometime between the end of 1853 and the end of 1855. It was during this time that Khyentse Wangpo, by then a respected lama, gave his public approval to the struggling treasure revealer. There is reason to believe that Chokgyur Lingpa attended a public empowerment at Dzongsar prior to this meeting, but the accounts of these events by Jamgon Kongtrul and Khyentse Wangpo are muddled and it is impossible to determine the sequence of events. In any case, over the two years Khyentse Wangpo gave Chokgyur Lingpa three empowerments, the result of which was that the young treasure revealer’s psychic knots were untied and he became capable – and, of equal importance, publicly authorized – to reveal treasure.

During the last of the empowerment rites Chokgyur Lingpa is said to have experienced a number of visions, including seeing Khyentse Wangpo asVimalamitra, and also the Nyingma deity Ekajaṭī, who gave him the prophesy that he and Khyentse Wangpo would together discover a treasure cycle called theDzogchen Desum (rdzogs chen sde gsum).

Two years later Khyentse Wangpo did indeed extract a treasure by that name, in collaboration with Chokgyur Lingpa. In January, 1857 the two lamas sanctified – “opened,” in Tibetan parlance – a new meditation site for Khyentse Wangpo, the cave known as Pema Shelpuk (padma shel phug), or Lotus Crystal Cave. This was in part a public ceremony, in which visitors were invited to witness the processes by which the cave and the surrounding hillside was mapped out as a supernatural site – they identified a spring of medicinal water, an overhang where Vimalamitra was said to have practiced, and so forth. Khyentse Wangpo also participated in the sanctification of Jamgon Kongtrul’s hermitage above Pelpung, Tsandra Rinchen Drak (tsa ‘dra rin chen brag) a month later.

Khyentse and Chokgyur Lingpa again collaborated on the sanctification of a site near Dzongsar, Rongme Chime Karmo Taktsang (rong me ’chi med dkar mo stag tshang), a cave site that became the hermitage for the monastery’s college at the beginning of the twentieth century. Over a two week period in November 1866, the two identified caves, propitiated deities of the site, and extracted treasure, the Tukgrub Dorje Draktsel (thugs sgrub rdo rje drag rtsal) from a lake, Sengu Yumtso (seng rgod g.yu mtsho), the Wild Lion Turquoise Lake. The Rongme opening was a major ritual event in the region, attracting the presence not only of large crowds of people, but also the King of Dege, Chime Dagpai Dorje (‘chi med rtag pa’i rdo rje, 1840-1898?). Rongme Karmo later offered Khyentse Wangpo’s disciple, the famous Nyingma lama Ju Mipam Gyatso (‘ju mi pham rgya mtsho, 1846-1912), a location for long-term practice; Mipam is said to have resided there for thirteen years.

When the group went up to the lake, a small body of water in the midst of a scree field more than 15,500 feet / 4,700 meters above sea level, Chokgyur Lingpa declared that a naga was guarding the treasure, and that everyone should be quiet so as to not offend him. Khyentse is said to have responded “What is there to fear in a naga? It is a worm! The so-called naga has no primordial existence. If he is there, I want to wake him up! I do not fear naga! If there is a naga, let it come here!” at which point he threw many stones into the lake. The others, obeying Chokgyur Lingpa’s command, refrained from throwing stones. Chokgyur Lingpa then attempted to retrieve the treasure using his robe as a lasso; when the lake water suddenly churned violently, Chokgyur Lingpa shrieked and fell back. Khyentse Wangpo slapped him, scolding him that as Padmasambhava’s representative he ought not be afraid. After the treasure was finally obtained, Khyentse Wangpo claimed that they succeeded because of the rocks he had thrown in, and on the way down the mountain he continued to throw rocks and people, claiming that everyone he struck was purified of their negative karma.

Khyentse Wangpo was a crucial player in the promotion of Chokgyur Lingpa’s treasures. Following Chokgyur Lingpa’s death in 1870, Khyentse Wangpo composed a brief biography of him in which his complete treasures were categorized into thirty-seven separate revelations, or “caskets” (gter sgrom / gter kha). He also took it upon himself to be a co-revealer of several of Chokgyur Lingpa’s treasures, most famously of the popular Barche Kunsel cycle (bar chad kun gsal), an assertion that should probably be taken as part of the elder lama’s process of affirming the treasure revealer’s legitimacy. Chokgyur Lingpa is said to have revealed this treasure in 1848; in 1855 the two worked together to decipher the treasure, an act which both Jamgon Kongtrul and Khyentse Wangpo describe as a merging of two separate revelations. Tradition has it that many of Chokgyur Lingpa’s treasure were initially fated to be revealed by Khyentse Wangpo, who passed them instead to the younger revealer.

Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo also participated in the production of Jamgon Kongtrul’s well-known “Five Treasuries” (mdzod lnga). According to traditional accounts, it was in a dream that Khyentse Wangpo had in 1861 in which he had a vision of a five-doored stupa, which signified to him that Jamgong Kongtrul ought to create “five treasuries.” Khyentse Wangpo proposed the Kagyu Ngakdzod (bka’ brgyud sngags mdzod) in 1848, declaring that the available liturgies for the Ngok (rngog) maṇḍalas were inadequate, and he repeated the request from Tibet, where he received a prophesy that Jamgon Kongtrul should undertake the job of collecting ritual manuals for the Kagyu tantras. In 1855 Khyentse Wangpo suggested the organization of the Rinchen Terdzod (rin chen gter mdzod), and he advised which treasures to include. And, while it was the Kagyu lama Dabzang Tulku Karma Ngedon (zla bzang sprul sku kar+ma nges don, 1808-1867) who asked for the root text of the Sheja Kunjab (shes bya kun khyab), it was Khyentse Wangpo who insisted that Jamgon Kongtrul write a lengthy auto-comentary. Khyentse Wangpo also worked with Kongtrul on his Damngakdzod (gdams ngag mdzod), a collection of religious instructions (gdams ngag). Only the last of the five, Jamgon Kongtrul’s collected miscellaneous writing, lacked input from Khyentse Wangpo.

Well before he put the idea to his colleague to create five great treasuries, Khyentse Wangpo had begun his own massive collection, the Drubtab Kundu (sgrub thabs kun btus), a compendium of Sakya sadhanas which he first began when he was staying at Sakya in the late 1840s. According to Jamgon Kongtrul, he gave the empowerment for the collection in 1852 at Pelpung for a group of about twenty prominent lamas. Khyentse Wangpo was the main inspiration and patron ofJamyang Lhoter Wangpo‘s (‘jam dbyang blo gter dbang po, 1847-1914) Gyude Kuntu (rgyud sde kun btus) in thirty-two volumes, a collection of initiations manuals for the 132 maṇḍalas of the Sakya tradition. According to Lodro Puntsok (blo gros phun tshogs) he also produced a collection of Lamdre Lobshe (lam ‘bras slob bshad) teachings in seventeen volumes, and eight volumes of songs and instructions from the eight practrice lineages (sgrub brgyud shing rta brgyad kyi zhal gdam gsung mgur), although this later collection is not included in the works associated with Khyentse Wangpo on TBRC. In addition, thirteen addition volumes of material not included in the above which constitute his personal collected works (bka’ ‘bum), which runs to twenty-four volumes. Khyentse Wangpo also famously authored a pilgrimage guide to Tibet, the U-tsang Neyik(dbus gtsang gnas yig), which has been translated several times into English.

It was largely on the basis of these impressive compendiums of teachings that Khyentse Wangpo is often referred to as a member of a so-called “Rime Movement.” It is more accurate to say that he embodied an ecumenical ideal (ris med) long cherished by Tibetan scholars, one of appreciating and exploring multiple traditions of Buddhism in Tibet. It is important to remember that Khyentse Wangpo was a Sakya lama whose primary ritual and literary activity was dedicated to that tradition, and while he worked closely with the Kagyu Jamgon Kongtrul and the Nyingma Chokgyur Lingpa, neither he nor his colleagues made any effort to merge traditions or initiate a new teaching institution.

Khyentse Wangpo served the Derge court for most of his career, both alone and together with Jamgon Kongtrul and Chokgyur Lingpa. He regularly went to the capital to perform rituals for the royal family and for the well-being of the realm. In 1859, for example, the three were in Dege to perform exorcism rites for the kingdom, at the request of the Queen, Choying Zangmo (chos dbying bzang mo, d. 1892) and her two sons, including the future king Chime Dagpai Dorje (‘chi med rtag pa’i rdo rje, 1840-1898?), during which Jamgon Kontrul records that Khyentse Wangpo “gave the most amazing lecture.” Jamgon Kongtrul took the opportunity to give the Queen, her sons, and his two colleagues the empowerment of the entire Nyingma Kama.

Later that same year Khyentse Wangpo participated in rituals designed to consecrate the ground for a new temple to the northeast of Dege, the construction of Chokgyur Lingpa had predicted would prevent the coming onslaught of the Nyarong War; owing to sectarian conflicts in Dege (the Sakya ministers would not allow the construction of yet another Nyingma temple, it seems), it was never built. During the war Khyentse Wangpo ransomed the safety of Dzongsar, although some buildings were burned by the Nyarong (nyag rong) chieftain Gonpo Namgyel‘s (mgon po rnam rgyal, 1799-1863) forces. For the most part he seems to have avoided the sort of involvement in the war that befell Jamgon Kongtrul, who found himself ministering to both Gonpo Namgyel and to the Tibetan forces from Lhasa who arrived to defeat him.

Khyentse Wangpo also drafted legislation, writing, again with Chokgyur Lingpa, a law restricting the killing of wild animals in the kingdom.

According to Jamgon Kongtrul, Khyentse Wangpo received all seven of the “seven transmissions” (bka’ babs bdun): Kama (bka’ ma), earth treasure (sa gter), mind treasure (dgongs gter), re-concealed treasure (yang gter), visionary transmission (dag snang), recollection (rje dran) and hearing lineage (snyan brgyud). This classification of transmission vectors appears to have originated with Khyentse Wangpo, who used it in his biography of Chokgyur Lingpa, and it serves as an organizing structure for most hagiographies of him as well. Among his best known treasure revelations were the Semnyi Ngalso (sems nyid ngal gso) cycle of Avalokiteśvara, revealed as earth treasure at Drakmar Drinzang (brag dmar mgrin bzang). His Drubtob Tuktik (grub thob thugs tig) was classified as a mind treasure, which came to him in a vision of Tangtong Gyelpo (thang stong rgyal po, 1361- 1485). Jamgon Kongtrul also includes in his biography of Khyentse Wangpo an event in which Khyentse Wangpo revealed thirteen treasure at the great mountain of Khawa Karpo (kha ba dkar po) when he was sixteen, with the help of a consort.

Khyentse Wangpo also is said to have recovered, via vision or dream, treasure cycles that had been lost over the years, reestablishing the transmission and making them available for inclusion in Jamgon Kongtrul’s Rinchen Terdzod. On the basis of his prodigious treasure-revealing activity, Jamgon Kongtrul counted Khyentse Wangpo as the last in a group of five kingly treasure revealers (gter ston rgyal po nga). His treasure name was Do-ngak Lingpa (mdo sngags gling pa).

Khyentse Wangpo is also remembered for greatly expanding Dzogsar Monastery. He built a fifty-pillar temple there, the Tashi Latse Utser Gonjang Lhakang (rdzong gsar bkra shis lha rtse’i dbu rtser mngon byang lha khang). He also built a small six-pillar temple, the Rigsum Lhakang (rigs gsum lha khang) on the plain below Dzongsar Monastery, known in local dialect as Khamshetang (kham bye thang), in 1871. This temple was transformed by the second Khyentse, Chokyi Lodro (‘jam dbyangs chos kyi blo gros, 1893-1959) in 1918 into the Khamshe monastic college (kham bye bshad grwa).

Jamgon Kongtrul presided over the funeral of Khyentse Wangpo, in early 1892, washing his body and preparing them for cremation. He performed a five-day Vajrakila rite in his presence, and, with the aid of the Tartse Khenpo and Loter Wangpo, performed three weeks of additional rituals. Jamyang Khyentse’s brother Kelzang Dorje, the head steward of Dzongsar, paid for much of the funeral. An elaborate reliquary was installed in Dzongsar, recently reconstructed together with much of the monastery.

Source; The Treasury of lives

Leave a Reply